A New York City solo practitioner has emerged from anonymity in a crowded market with newsworthy cases, an active presence on LinkedIn—and a willingness to change along the way.

When John Scola launched his solo New York City law practice, fresh out of law school and several months after passing the bar, his marketing plan was about as no-frills as they come. He hadn’t expected to venture out on his own so soon, but two stints working for other lawyers had quickly proved to be insufferable, leaving him no other good choice.

No-Cost Startup Marketing

His first move, on the advice of a colleague, was posting an ad for his services on Craigslist. “I had no idea people hired lawyers off of Craigslist, but I didn’t have any money for advertising and at the time it was free,” Scola says. The listing generated “occasional calls,” which was good enough at that point in his career but not worth continuing. Another no-cost marketing gambit brought in more work. “I would go to landlord-tenant court in Brooklyn in a suit and stand around looking like I was supposed to be there,” he says. “I wasn’t a landlord-tenant attorney but people without lawyers would hire me to do something for them. That’s how I got started.”

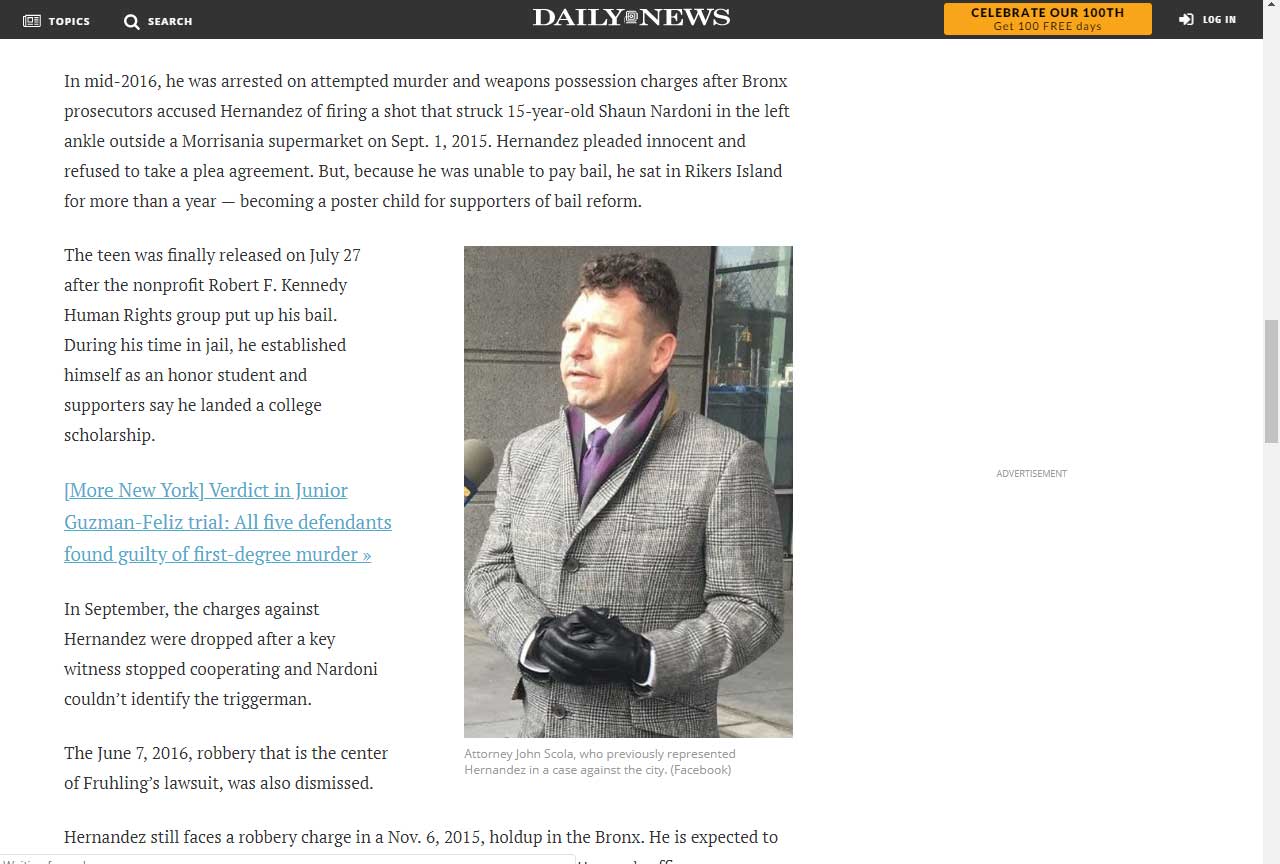

Half a dozen years later, Scola is no longer laboring in anonymity. His cases regularly end up in the daily news in New York City, as he shows in an array of links on his law-practice website. Most recently he made headlines with a suit against the city school district on behalf of a family claiming that their daughter committed suicide after being bullied at school. Another batch of cases involving alleged corruption in the New York City Police Department landed Scola in a starring role in a documentary called Crime + Punishment that was picked up by Hulu after sweeping up awards on the film festival circuit, including a Sundance special jury award for “social impact.”

Scola would be the last to call himself a star. His practice, which he is focusing these days on personal injury and employment law, is “nowhere near a finished product,” he says. His approach to law-practice marketing is also a work in progress. He has moved up from Craigslist to LinkedIn, where he is focusing most of his marketing efforts these days. But he confesses, “I’m still trying to figure out what works.” To get where he is now, “I got lucky, to be honest with you.”

Going solo so soon after passing the bar wasn’t Scola’s original intention. Getting experience and mentoring in a law firm setting would have been his preference. He had worked for a personal injury firm during law school, which was “very stressful,” but he stuck it out on the strength of a promise of a job once he graduated. He didn’t learn until then that his starting salary would be $35,000 a year, a “crazy low” sum in New York City. So he switched to working for another lawyer who promised $60,000 a year–on condition that he commit to responding within 15 minutes to any email that arrived any time between 6 a.m. and 2 a.m. That, too, was intolerable. But in his first lucky break, he ended up with a number of referrals from that attorney, who had burned out on practicing law.

Media Coverage Pros and Cons

His involvement in the case featured in Crime + Punishment started when a private investigator he had used on cases told him that some minority officers in the New York City Police Department were complaining that they were pushed to meet arrest quotas. The quotas were not only illegal, but they were higher in minority neighborhoods, and thus discriminated against minority officers who were assigned to work undercover in those communities. The officers faced retaliation when they complained, the suit that Scola filed contended. It eventually became a federal class action with a dozen named plaintiffs, known as the NYPD 12.

That case, and the press coverage it generated, boosted Scola’s profile. A stream of clients suing the NYPD for false arrest followed, bringing him cases with varying degrees of merit. “I don’t do many of those anymore because they are too unpredictable,” Scola says. “You could have the best case in the world and the kid might be rearrested which really torpedoes the case. It’s a lot of work for being so unpredictable,” Scola says. “Over time I became a lot more selective in deciding which cases were viable.” He also realized that his practice was too narrowly focused. “I learned the lesson that I needed to be much more diversified and develop more streams of business,” he says. “I’m now trying to do that.”

Scola has also learned that press coverage is a mixed blessing. “Cases that are in the news can be lucrative, but I am much more reluctant to talk with reporters now than I used to be,” he says. “It depends on the case and who your client is, to be honest. I do a lot of false-arrest cases. When it comes to those types of cases you have to be very careful who you talk to.”

Scola was comfortable with the documentary filmmakers following him and his clients around with cameras rolling, but he doesn’t jump at every chance to get in front of a camera. He turned down an invitation to appear at a press conference to talk about the case of the girl who was bullied at school. The press conference was about gender equality in education and the city budget. “I don’t know enough about those issues and I could hurt the case,” he explains.

Raising His Profile on LinkedIn

People who call because they saw him in the news aren’t necessarily the best prospective clients anyway.

Referrals from other attorneys have been much more productive, a realization that has influenced where he tries to be seen these days, and that for now is LinkedIn. Investing just a little time every day on the professional networking site, Scola has built an impressively large following.

For a year and a half every day he clicked on as many of the site’s “suggested connections” as LinkedIn would allow. “I would keep clicking them until I was maxed out for the day. It would take literally like a minute. A year and a half later, I now have 19,000 connections,” Scola says. He’s not sure how many of them are lawyers but he suspects that about half of them are because most of the suggested connections are in law-related professions, he says. “I don’t know how to make money off it yet. I know theoretically I could post ads or get referrals, but whenever I figure out what to do with that, I already have a substantial database of connections.”

On LinkedIn, he frequently “likes” and share posts. He has joined several dozen groups ranging from alumni associations to bar sections to networks of personal injury and medical malpractice attorneys. And he posts comments about his own cases and thoughts on practicing law.

A casual remark about attorney referrals has been his biggest hit on LinkedIn so far. Scola remarked that he had gotten a call, and would soon be meeting, “an attorney who was looking to set up a mutually beneficial referral relationship between his firm and mine.” Scola added, “For those who are looking to do something similar, even if you’re just an associate with a lot of friends who need lawyers, please feel free to reach out. This is an easy way for attorneys to mutually profit and get clients the assistance they need. As attorneys, we fight enough with each other, it’s good to have some allies out there.” Hoping to extend whatever reach it might have, he added the hashtags #lawyers, #attorneys, and #justice.

For reasons that remain something of a mystery to Scola, who had posted many other items that got no response at all, that particular comment got 16,000 views, dozens of likes, and five comments. In a follow-up post three weeks later, Scola reported that it had led to “meaningful phone conversations” with 10 attorneys, and seven referred clients: five employment cases, a criminal case, and the wrongful death case stemming from the schoolgirl’s suicide. He, in turn, passed on four cases that he was not equipped to handle himself. Scola reiterated his invitation to other attorneys to reach out. “Even if you don’t have anything specific to refer, starting new relationships will allow you to be on the lookout for different types of matters that can be easy money for both sides,” he wrote, attaching to that post the hashtags #lawyershelpinglawyers, #referralnetwork, and for good measure #happyvalentinesday.

“I have no idea how LinkedIn works but I think it’s probably more productive for work than Twitter or Instagram or other social media sites,” Scola says. “It’s not a main source of business, but I spend maybe five or 10 minutes a day playing around with LinkedIn. It’s interesting to see what pops and what doesn’t.”

Scola has tried advertising in other outlets. He ran an ad for six months in a paper called Caribbean Life after a lawyer acquaintance told him he got a decent response from an ad in the paper. “It did nothing for me,” he says. But he is considering testing the waters with an ad in another publication. Since he has represented a number of police officers in employment cases, he is considering “possibly a cop magazine or a cop newspaper, but I’m not sure,” he says.

Meanwhile, he is adding still other lines of work to his portfolio, including serving as general counsel for a small startup in the cannabis business called Outspoke IO, Inc., which was launched by a law school friend of his. “I wouldn’t be opposed to doing more of that kind of work,” he says. “It could generate steady income that would offset periods of waiting for cases to settle.”

Adjunct Professorship

For fun, and yet another stream of income, Scola has been teaching as an adjunct professor at his alma mater, New York Law School, since the beginning of 2019. “I saw an advertisement seeking a teacher for a class that I took in 2011,” he says. “I wrote a cover letter and updated my resume, which I hadn’t done for seven years, and in the end I got the job.” He helps a tenured professor teach a class about interviewing, counseling, and negotiating in a simulated case involving a suit against a school district. “The students conduct interviews with the ‘client’ that are recorded and we go over them later. They run the case all the way through, and then they simulate negotiating for the other side,” Scola says.

“It’s a decent amount of work and I don’t get paid that much, but it’s very enjoyable. It’s also reinvigorating in a lot of ways,” Scola says. “The kids are really excited about becoming lawyers. And I realize I have much more experience than I thought I did, which is pretty cool.”

The gig also helps him keep up his people skills, which he learned early on, standing around in a suit in landlord-tenant court, was a key to making it. “You have to go out and talk to people. Just go out and do it, and learn on the fly,” Scola says. “You can’t be shy. You’re a lawyer but you’re selling legal services, and you have to talk to people and you have to be personable. I think some people picture lawyers as very rigid and stern. You don’t want to come across that way. Make sure you smile.”

Scola adds, “Also make sure you communicate well with the client. Keep them informed. It’s okay if the case is not going to be great but you have to be upfront with them about that. Don’t overpromise. I can’t emphasize that enough. A lot of lawyers overpromise in order to get cases. That’s a fool’s game,” he says.