Volunteering to help the needy built this Hawaii attorney’s caseload.

Two internships during law school at Yale a decade earlier had a major influence on the shape of the solo disability law practice that Diane Haar opened in Honolulu in 2011.

At the Natural Resources Defense Council, a nonprofit public interest firm, she lamented the effort that had to be spent hunting for money and “didn’t like the idea of getting shut down just because the grants don’t show up.” She was in another internship in the environmental crimes division of the Justice Department when a new administration took office, “and all of a sudden they weren’t allowed to pursue certain cases.”

Haar wanted to do public interest work. “But I didn’t want politics to be able to change what I did, and I didn’t want funding to be able to change what I did. If I was doing something good, I just wanted to be able to do it,” she says. That’s where the idea for Hawaii Disability Legal Services, LLC came from. “I didn’t necessarily have the idea fully formed when I started. But I wanted something that looks a lot like a nonprofit and feels a lot like a nonprofit but funds itself.”

Haar had to wait eight years after law school to try her idea out. Her husband was in the military and they moved too often for her to get anything started until then. When he retired from the military and accepted a job in Hawaii, she took the Hawaii bar after they moved to Honolulu, got licensed and launched a practice in 2011. Six years later, business has grown to the point that she has taken on two paralegals and an accredited disability representative in a satellite office on the big island of Hawaii.

‘Looks Like a Nonprofit’

‘Looks Like a Nonprofit’

Haar and her staff at Hawaii Disability Legal Services fulfill their public service mission with a busy calendar of bar activities, legislative lobbying and pro bono appearances at homeless shelters, senior citizens centers and an array of other venues.

In one recent two-month period, they offered help on disability claims to walk-ins at a rural community center and at a Veterans Administration event for homeless veterans, attended a faith-based summit on homelessness, helped train volunteer attorneys at an Office of Veterans’ Services conference, spoke at a state bar event on leveraging technology, and attended a legislative forum on services for the disabled.

At community clinics, in addition to answering questions and helping people with paperwork, Haar says, “I triage people. I have a good idea what benefits they might be entitled to, where they need to go, and where they can get medical care. I have the phone number for the attorney referral line, and maybe names of attorneys I trust to handle other areas of law.”

Haar also takes on other cases pro bono, such as administrative appeals of especially egregious VA reduction-of-benefits cases and potentially precedent-setting cases involving the rights of the disabled and homeless.

How the Firm Pays Its Bills

Meanwhile, Hawaii Disability Legal Services pays its bills by collecting a share of the back pay that the firm’s clients receive in denial of claims cases and awards of attorneys’ fees in cases won in federal court. “I never actually send my clients a bill,” Haar says. “I don’t take anything from them going forward and though I work on all the islands, I don’t charge for travel expenses, medical records or anything like that.”

The “private public interest” model has allowed her to do good while making enough to sustain and expand her practice. It has also had another benefit that was unexpected but has been crucial to her success: winning acceptance in Hawaii, a famously insular state. “I actually go to every island and I do just fine despite the fact that I have only been here since 2010. It’s just shocking,” Haar says. “This shouldn’t be happening. But they are okay with me.

“What I found is that by being willing to sit down and talk to and help anyone, I was making myself a member of the community. I could not have done it any other way.” Haar says she loves working with the homeless and other people who need help, “telling them about their rights, telling them about the things they could do for themselves. It just feeds something in me. I learned kind of on the backend that that was marketing. I learned it by seeing the results. It is what built my practice.”

Launching a Private Public Interest Practice

To be sure, it took her awhile to attain even a modicum of success. “In my first year I made, before deducting expenses, about $20,000. Everything is on a contingency fee basis and I don’t get anything unless I win.” That can take a long while. Social Security cases can go two years or more. A veteran’s benefit case she picked up has been going on for 10 years.

In her first couple of years, before she had much of a caseload of her own, Haar made the rounds of legal aid groups in Hawaii, “sticking my hand out, introducing myself and offering to do pro bono cases.” That connected her with nonprofits and other groups that welcomed her offer to give clinics and seminars on the rights of the homeless and disabled. “As attorneys we are not allowed to approach people who we know need our help and basically thrust ourselves on them. But seminars are one of the ways you can be there in a different way. You are basically explaining to people what their rights are and you are, of course, a person they could go to later if they need further help. Even if you can’t help them, if you can send them to someone who can, they will remember you. And when their friend comes up and actually needs your help, they will send their friend to you.”

Word-of-Mouth Advertising

Word-of-Mouth Advertising

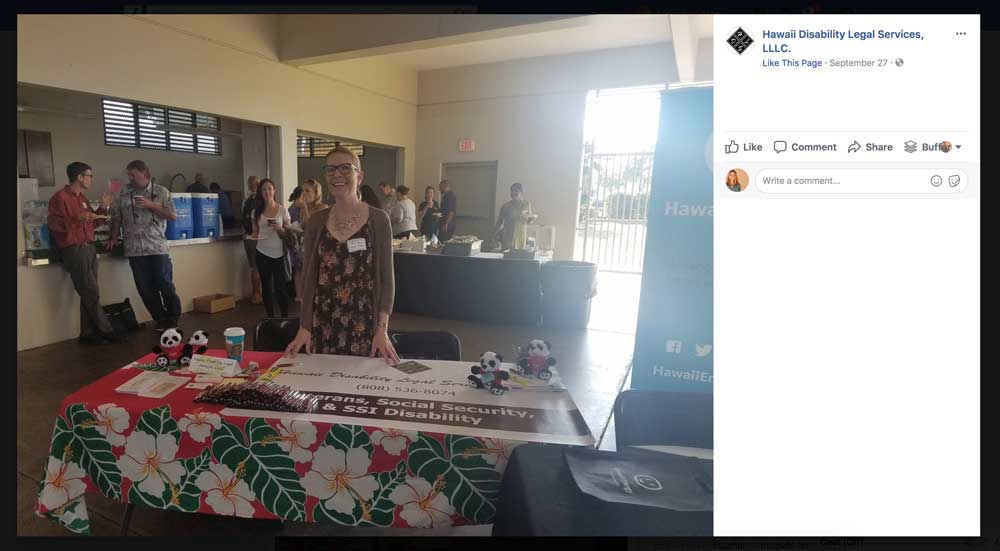

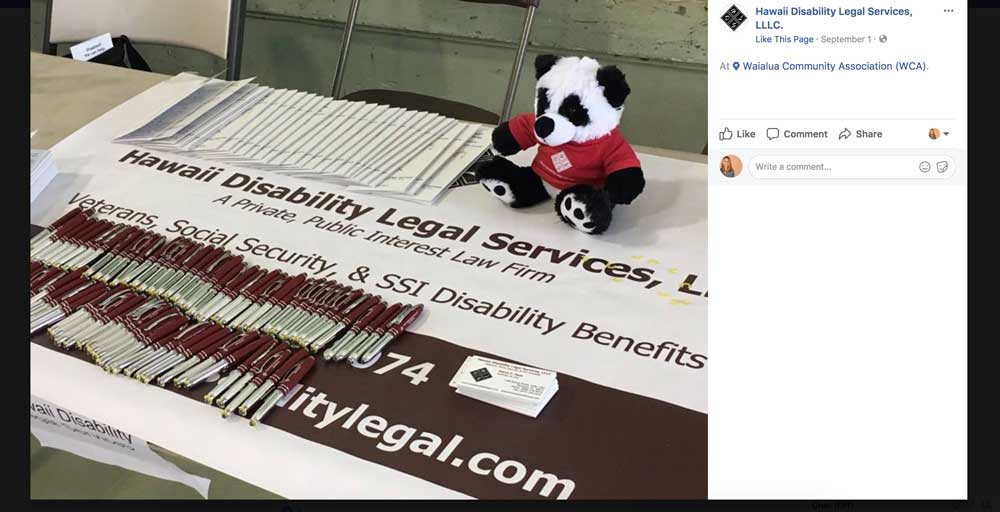

To facilitate future connections with her firm, Haar has a couple of eagerly sought-after handouts bearing the firm’s logo, name, and phone number. A sturdy pen with a built-in flashlight is one big hit. The idea came to her when she received a free sample from a marketing company. “I work in homeless shelters. Some of them are big rooms with a lot of beds. I also work with people who are camping outside. I thought, how handy: a flashlight,” Haar says. “But I didn’t know they would take off the way they have. I have homeless guys coming into my office and asking if they can have a pen.”

She also hands out stuffed pandas with her firm name and logo on a shirt. She ordered the first batch to hand out at a conference for disabled kids but has found that adults like them as well. “What I do involves a lot of stress for grown-ups,” she says. “I have a lot of tears in my office, and these things are awesome for pretty much everyone. They are supersoft and such a source of comfort. And they seem to have really taken off. Whenever I go off with the pandas, I never come back with any. And I’ve only seen one with its shirt ripped off.”

The handouts are more effective as a marketing tool than a website in her state, Haar says. “I hate to say it but Hawaii really is Podunk. We’re out in the middle of nowhere. You don’t need to have an online presence because people ask their friends and neighbors first,” says Haar, whose spare, static website reflects that thinking. “Most of my referrals are word-of-mouth. It’s homeless, its veterans. Doctors and therapists are huge. It’s friends and family.”

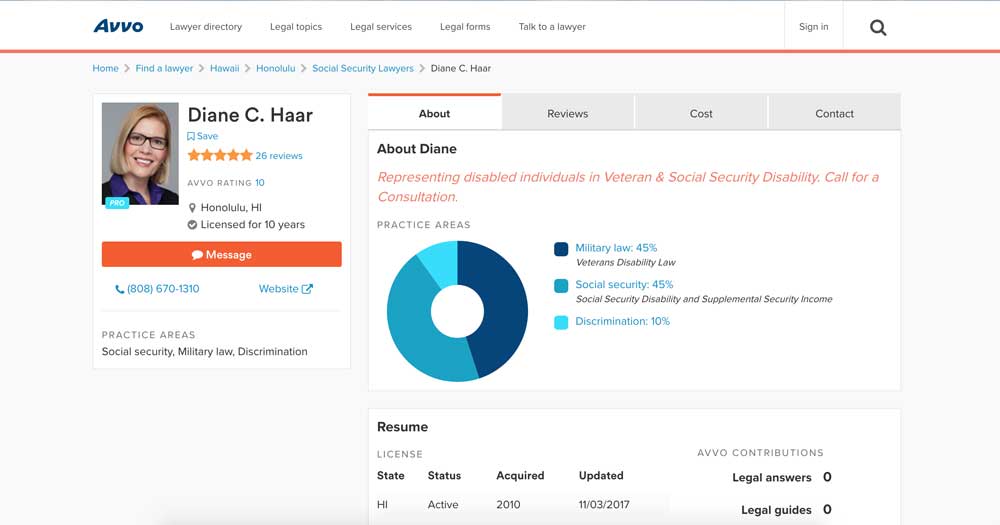

She has a Facebook page only because one of her paralegals has taken the initiative to start and maintain it. “It’s a great way to keep track of things but it’s not necessary here.” The one online service that has been useful in drawing business is Avvo. “Even before I claimed my profile, one of my clients left a positive review, and just from that, I started getting clients. That surprised me because Hawaii is like a small town. We don’t have bordering states. Our population isn’t that large.”

Fitting Practice to Personality

Although her online presence is minimal and rudimentary, Haar is no Luddite. To succeed in a low-cost law practice, she says, “leveraging technology is the way to go. If you can keep everything in the cloud it is a lot less costly.” She uses the CallRuby receptionist service, the Clio case management system, Dropbox, Google Calendar and various other Google apps, using the paid versions of those tools for enhanced security.

“I feel really fortunate that I’ve been able to leverage technology because it allows me to practice from anywhere and it also allows me to manage the work-life balance I want,” she says. “Now, all I do is pick up my laptop, my mobile printer, and my mobile scanner, throw it in a bag and I can set up my office anywhere in the islands.”

The private-public-interest model has freed her to practice the kind of law she has always wanted to practice, Haar adds, defying the warnings of some of her mentors. “I have gotten a lot of advice over the years from other attorneys, particularly the older women attorneys, who told me, you have to be more of a bitch, you have to be tougher, you have to be more of a curmudgeon. But I decided I was going to operate more on the basis of my personality and this just fits so well. I don’t think I would be happy any other way.”

“There is no one type of marketing that works for everyone. But I think for certain types of attorneys, this is a wonderful model. If you’re going to run your own show, you should fit your practice into who you are and what you are comfortable with because if you’re running your own show, you’re going to be doing a lot of running.”